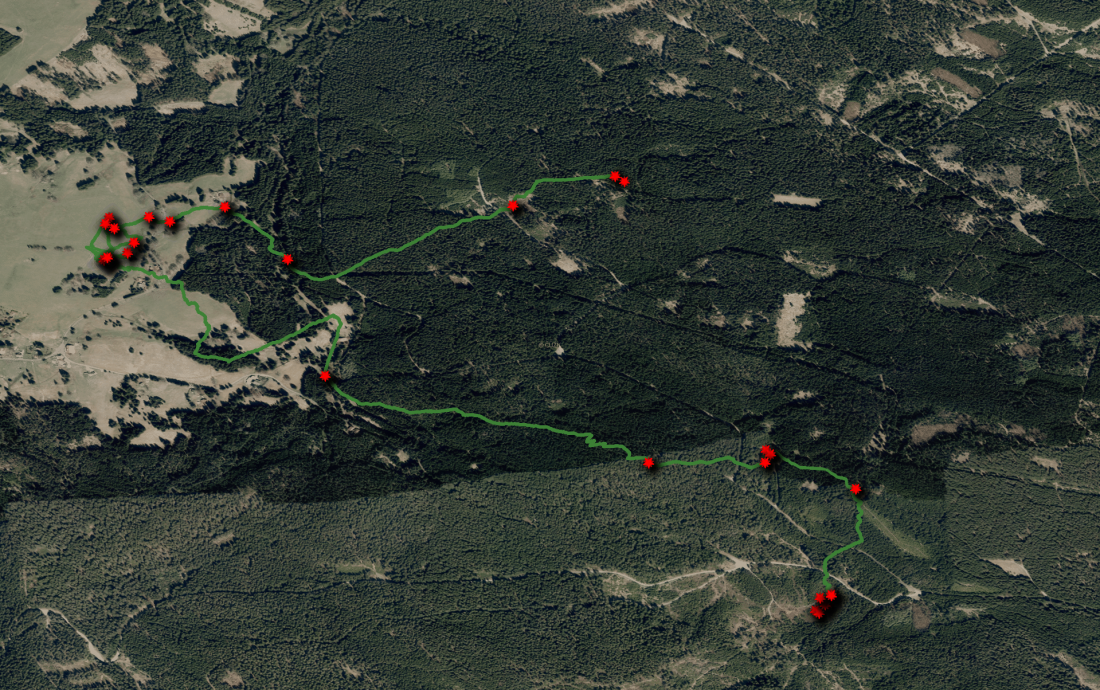

We have been dealing with the spatial activity of game at the Department of Game Management and Wildlife Biology for a long time. We track animals using GPS telemetry and camera traps. Wild boar, red deer, sika deer, roe deer, foxes, wolves and lynxes are currently being monitored.

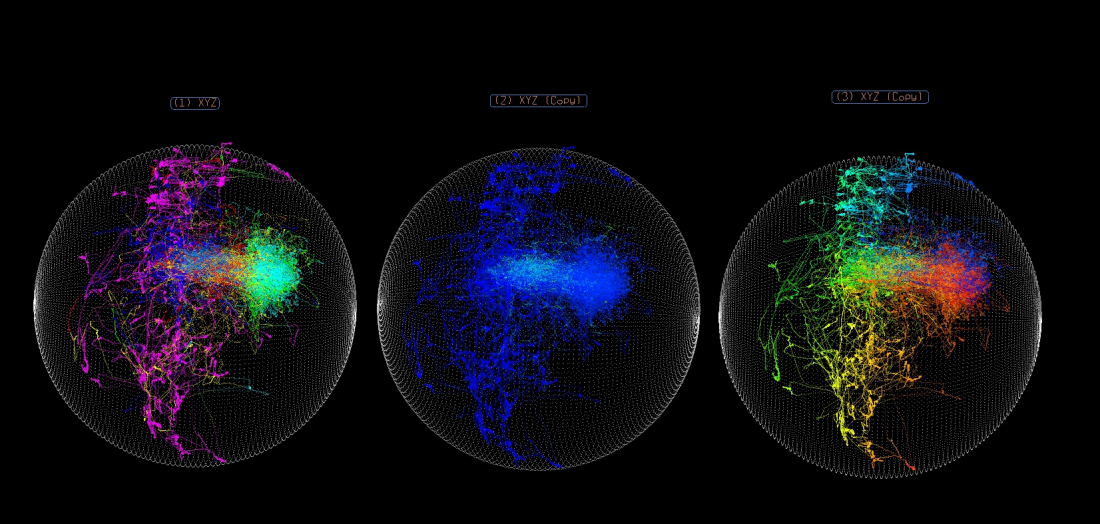

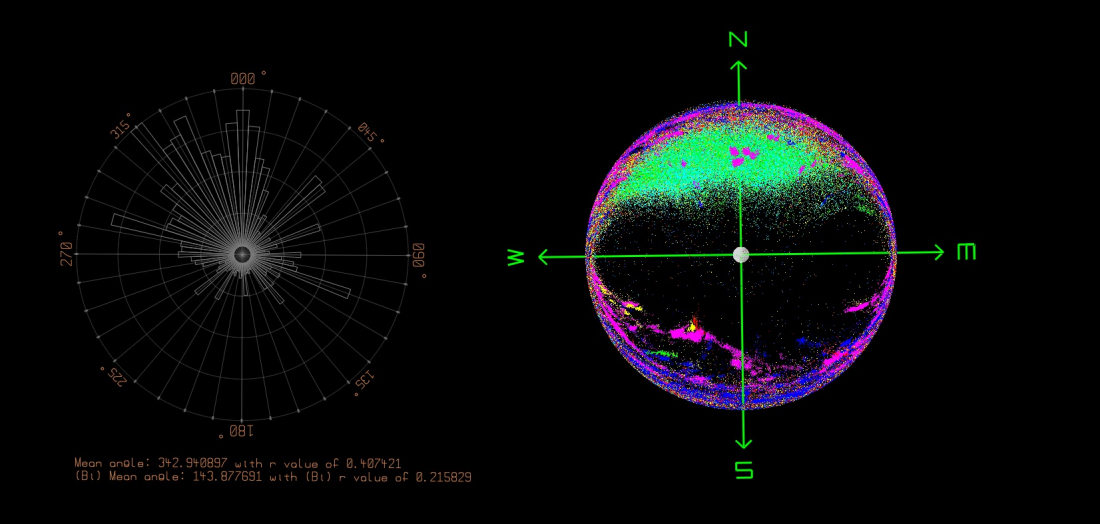

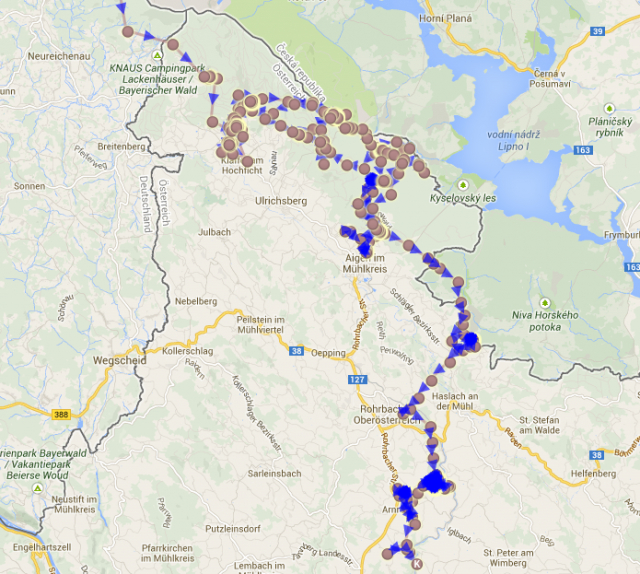

The method of classical radiotelemetry is used to monitor foxes, in which it is necessary to determine the position of the animal using a VHF signal and subsequent triangulation. This is very time consuming, and data from classical radiotelemetry are not very accurate. For other species, we use GPS (Global Position System) collars, which record the position of the marked animal with an accuracy down to several meters. We do not record their position continuously, but at predefined intervals (generally once every half hour). In cooperation with the University of Swansea, UK, we added biologging sensors to the collars, with which we are able to distinguish the animal's behavior and energy consumption, as well as reconstruct the path between two GPS points. The collars are equipped with a GSM module and contain a classic telephone SIM card, through which this information is transmitted online to our computers. The telemetry team has over 130 GPS collars.

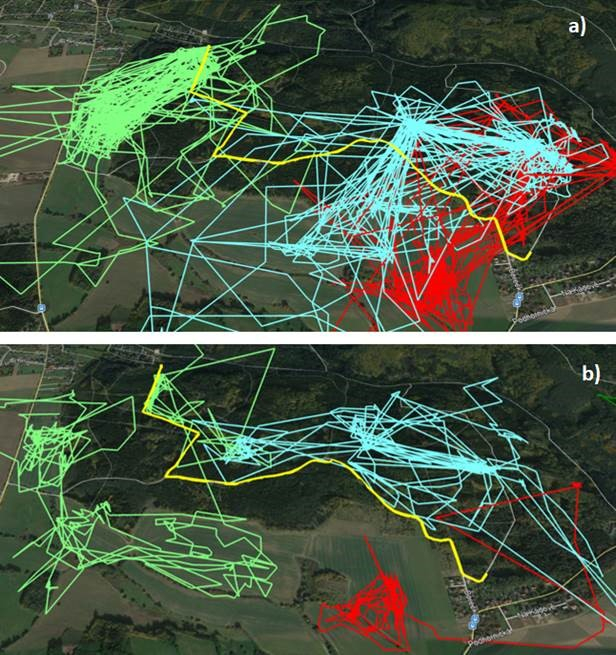

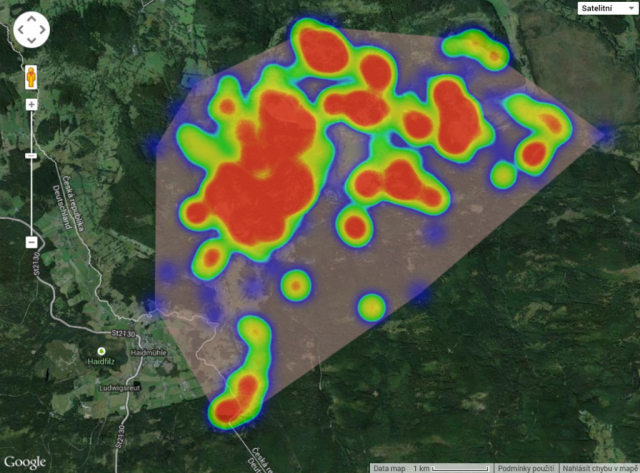

The data are subsequently evaluated using basic methods such as MCP (Minimum Convex Polygon), Kernel home range, or the environment, reactions to disturbances, etc. are evaluated.

In the analysis of the spatial activity of game, we test several important areas: cognitive behavior after animal translocation and the ability of homing (i.e. returning home); the effect of feeding and the availability of natural food; the effectiveness of different types of barriers to spatial activity (electric and odor fences); the affinity of wild boars for carcases in the environment as a potential source of African swine fever virus; the effect of anthropogenic disturbing elements (hunting, tourism, leisure activities, etc.), and many other interesting topics.